Kazimierz Square

“Karen Chase’s poems modulate from the humorous to the erotic and then to the elegiac. All is held together by her skill and intensity. No line sleeps in these poems in which moments of real experience are isolated and made incandescent.” -Billy Collins

Looking for the second book of CavanKerry Press’s initial season, the publisher turned to admiring notes left by the distinguished poet Amy Clampitt before her death about the bold, intense poems of Karen Chase. Joan Handler, the publisher, asked Chase to make a book of these rich, earthy poems, culminating in what Clampitt called the “demonic astonishment” of Chase’s long poem “Kazimierz Square.” Using Sappho’s motto, If you are squeamish/Don’t prod/ the beach rubble. Chase digs into the past for what can illuminate the present, “armed” always, as Andrei Codrescu notes, with a “shield of humor.” Sometimes with her heart in her mouth, but always fearlessly, she explores the world in lines of an aesthetic rigor that will win her readers and thrill those who are already among her admirers. Billy Collins has called this remarkable volume “humorous…erotic…[and] incandescent.” –Molly Peacock

Indie Poetry Book of the Year Award 2000 – ForeWord Magazine shortlist

Reviews

“A poetic voice of earthy directness and visionary power” -from the foreword by Amy Clampitt

“Lyric and eros armed with a tattered shield of humor – Karen Chase is present in her life and our times.” -Andrei Codrescu

“Karen Chase’s poems modulate from the humorous to the erotic and then to the elegiac. All is held together by her skill and intensity. No line sleeps in these poems in which moments of real experience are isolated and made incandescent.” –Billy Collins

The San Diego Union Tribune

Publishers Weekly

The Miami Herald

ACM

The Berkshire Eagle

The Berkshire Eagle (commentary)

—————————————————————–

The San Diego Union Tribune

Poetry remains essential, giving balm to the soul

September 30, 2001

Carmela Ciuraru

In the wake of the tragedy and grief that has affected our entire nation, we need our poets more than ever. Regardless of whether its tone is droll or elegiac, poetry clarifies and articulates our emotional states like nothing else does — with the exception perhaps of music. When everything seems lost to us, what could be more comforting than (to cite just one example of the power of verse) these lines from Ezra Pound: What thou lovest well remains / the rest is dross / What thou lov’st well shall not be reft from thee / What thou lov’st well is thy true heritage…?

Below are some recently published titles that differ greatly in style and voice, but that all serve to remind us why poetry is essential reading.

Perhaps the most anticipated collection of the fall, Billy Collins’ “Sailing Alone Around the Room: New and Selected Poems” (Random House, 172 pages, $21.95) is the poet’s first book with a major publishing house….

The second title issued by CavanKerry, a New Jersey-based independent press, Karen Chase’s “Kazimierz Square” (74 pages, $14), offers visceral poems of longing and anguish. In “Venison,” Chase describes in sensual, startlingly vivid language the aftermath of a successful hunt. As the deer is split open, the smell is not rank, and peeling it is simpler than skinning a fruit.

The speaker finds herself excited by the butchered meat, new with blood / stray hair from the animal’s fur. Cooking and eating the venison leads to the devouring of a lover’s body: Throughout the night, we consumed and consumed. (It’s no wonder that Chase’s debut opens with this epigraph- fragment from Sappho: If you are squeamish / Don’t prod the / beach rubble.)

In other poems, the body aches with unfulfilled desire and stark memories of loss. The body remembers what the mind forgets, she notes in “Why Anything,” in which a woman is left cold by her inscrutable lover. Whatever it was, I did dirty work just to be near, she recalls sadly, bent forward, backward, over the bed, stooped so you could fatten on me. But after sex, her lover’s eyes suddenly got like brass, sunk away.

Chase’s realms move easily from the erotic to the historic. In the collection’s moving, elegiac title sequence, she travels to the old Jewish quarter in Krakow, where it is 1942 and a trumpeter’s notes are cut short / to mark the moment he was shot, and where the wind sends the rain sideways / carries stink into everyone’s nose.

In the poem’s third section, Chase’s style turns Plathian: I bite the thick air / I bite at nothing / I lick the savage ground / My mother is ash in the ground. Aside from a few casual, unremarkable poems, “Kazimierz Square” as a whole is an intense, impressive collection, full of excavations that yield both pleasure and terror.

Other recent and noteworthy titles: “Bloodlines” by Fred D’Aguiar (Overlook Press), a novel-in-verse about America’s shameful history of slavery; “Darling” (Grove Press), by the poet and biographer Honor Moore, which offers meditations on memory and desire; and “Night Picnic” (Harcourt), the latest collection by Charles Simic, which beautifully evokes the mysteries of both rural and city life in brief, imagistic poems.

Carmela Ciuraru is editor of the anthology “First Loves: Poets Introduce the Essential Poems That Captivated and Inspired Them.” She lives in New York City.

Copyright SAN DIEGO UNION TRIBUNE PUBLISHING COMPANY, September 30, 2001

———————————————————–

Publishers Weekly

November 6, 2000

Poet, publisher and clinical psychologist Joan Cusack Handler (no relation to the Hollywood Cusacks) named the New Jersey-based CavanKerry after the two Irish counties from which her parents came. Chase’s debut is the second title for the press, and it begins with poems set a bit further east, in Poland, where present-day peasants, poverty and mud suggest at once the logic of fairy-tale worlds and the specters of the Holocaust. All these realms merge in the title sequence, where the agitated poet imagines herself transformed to a “brown-furred wild boar.” Chase’s short lines and transient stanzas at once seek casual appeal and chiseled grace in a variety of styles and forms, and use them to talk about differing kinds of experience: poems about Italy don’t sound like poems about Poland, and her pair of poems on a visit to Iceland adopt a starker attitude still. Other works, though, seem tossed off, dependent on simplistic concepts: “The A B C of What I’ve Been Called” zips through “Baby, Buddy, Bitch and Babe” before settling on “Zenas Block’s daughter.” The late Amy Clampitt, in a short introduction, praises Chase’s “raw power,” and the stark alertness and verbal clarity of the poems should attract fans of Marie Ponsot and Elizabeth Macklin, while her particular subjects may give her an audience broader still. It’s an apt book for a press that aims to “introduc[e] a literary audience to books that focus on both the aesthetic as well as the psychological impediments to the expression of voice.”

———————————————

The Miami Herald

Sunday, November 12, 2000

Arts Section

In her introduction to Karen Chase’s new collection, the esteemed late poet Amy Clampitt writes: “Painting and photography are things Karen Chase does well; so are fishing and cooking. I never met anyone quite so vividly and rewardingly at home with putting together a meal.”

So in Kazimierz Square (CavanKerry, $14 in paper), we are not surprised to find poems that make room for spuds, venison, herring, schnapps, clams, apricots, boiled peanuts, salmon, squid, pears, mushrooms, beets, peas, plums, tomatoes and – so it all goes down smoothly – butter and wine. But Chase proves she can put together feasts for other senses as well. There are poems about stubborn sheets and heaped quilts, about a Polish flea market where “one man held up one shirt/ for sale, all day . . .,” about the day after a parent dies (“I am wearing my mother’s old jacket./ Like never before, she’s close”).

Chase writes and teaches in western Massachusetts, but because she will be headed this way for the book fair – and because it is about food – we offer this poem:

SOUTHERN VISIT

I’m a northerner on an extra chair.

Some girl in her 4th month is starting to show shape,

her mother’s traveling north with a suitcase of oysters.

They chew on gristle, pick bones so clean they’re white.

Dinner takes a long time.

If I lived here, I’d stay in bed late,

sit at breakfast with my mother and sister,

take turns telling nightmares like they were stories.

We’d each have three cups of coffee, share a plate of doughnuts.

So what if we’d hear a car lurch out front.

I’d meander downtown, eavesdrop on the bar sounds.

I’d watch men play dominoes outside a store,

wonder who the floral offering on the pickup is for.

I’d throw back my shoulders, be aware of my ass,

pout the right amount.

I’d notice a man who’d never been in town before,

notice his knife as he peels a pear.

Marking the drive with which he strips that pear,

I’d catch sight of a bed with pink covers through a window,

look around for an exit and a souvenir.

All content © 2000 THE MIAMI HERALD and may not be republished without permission.

—————————————–

ACM

ANOTHER CHICAGO MAGAZINE

Number 38 2001

KAZIMIERZ SQUARE. By Karen Chase. CavanKerry Press Ltd, Fort Lee, NJ, 2000, 88 pages. $14.00. Paperback.

Amy Clampitt writes in the foreword that Chase’s writing is “an instance of the poet in the grip of the poem, rather than the other way round,” and I think we can agree with Clampitt. Chase has a beautifully stark and sudden way of writing, sometimes reminding you of the fervor of Sylvia Plath and other times of the earthy humanism of Charles Simic. Through this combination of styles, Chase is able to help you embrace a poem rather than feel alienated. This can be seen in the first poem of the collection, “Venison,” where she writes, “you cloaked me in your large arms, then / went for me the way you squander food sometimes.”

Helping to draw us into a poem is the way Chase shows us the parallel between the individual and that which is more universal. This is best illustrated in the poem “Fever.” On the surface the piece is a basic retelling of a childhood affliction with polio and the accompanying fever. However Chase is able to transcend this experience and guide us from an experience that is very singular and personal to something more epic. She writes: “From then on, everything was before or after like war.” With one line Chase is able to encapsulate the dual realities of the moment. She is able to sweep together the feelings of one person in the throes of illness, with the historical sense we all feel as time is measured “before or after like war.”

While not as emotional or intellectual as most of the poems in Kazimierz Square, I have to admit that one of my favorites is a piece titled “This Is What It’s Like Going to a Language Poetry Poetry Reading.” The poem deals with the agony of sitting through a language-poetry reading, where you are liable to hear lines such as “the, the, the the/back.” Chase’s poem ends with the fantastic image, “You think of killing her [the reader]. You think she’s killing you. You/think of so much murder, you’re scared to go to your car in/the dark.” Even here in a seemingly simple amusing poem, Chase’s ability to highlight the duality of a phrase stands out. We are at once struck with the humor of the situation, yet halted by the admission that people today are still “scared to go to your car in/ the dark.”

Often in reading Chase’s work I find myself commenting on how true a statement is. She has a great way of illustrating experiences we can all relate to. For example in “At the Hospital,” a poem which reflects on a first day back to work after her mother’s death, she writes: “I am wearing my mother’s old jacket / Like never before, she’s close.” Chase sums up many emotions and images with those few words. We imagine how that jacket is smelling or feeling to Chase. We are right there with her as she holds this jacket and lives through the singular emotions a scent or touch can bring to life, and along with Chase, we are able to marvel at the phenomenon that often something is closer once it is gone.

Kazimierz Square is the second title from the emerging CavanKerry Press and the first book publication for Karen Chase. Chase uses the title poem to end her collection. It is a lengthy nightmarish poem which encapsulates images of death, life, culture, sexuality, and klezmer music all at once. Chase’s collection is sure to engage and challenge anyone looking for an awakening of lyricism and emotion.

-Michele Walker

—————————————–

The Berkshire Eagle

Karen Chase’s poetry fears little, illuminates the unusual

October 8, 2000

by Trudy Ames

Filled with, unusual and sometimes terrifying landscapes, brilliant colors and erotic pleasures, Karen Chase’s first book of poems, “Kazimierz Square,” takes you to places you only dare to fancy in private.

Chase is fearless when it comes to the articulation of the imagination. Her work echos the philosophy of the dark romantics who advocated that the imagination is limitless and that art is the right place to share our best as well as darkest wanderings.

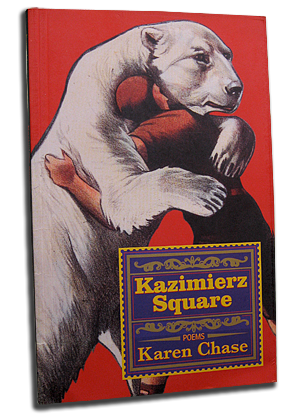

From the cover illustration of a man hugging a polar bear, to the final poem, which gives the book its title, the reader journeys by way of irresistible rhythm and well-crafted syntax to exotic places that somehow still feel like home.

The book is split into four sections, beginning with poems that recall personal and provocative moments, experiences painted in such a way that the reader is quickly inside the poem rather than an observer. There is a wide range of topics, and never does the sentiment become self-indulgent or morose.

In the highly visual “Fever,” we travel with “The arsonist,” who is “meandering down the neck of white washed air,/clad in red leaves and plaid bathrobe,/flammable nightshirt underneath,” into the world of the 10-year-old speaker, who is “rapped with polio” watching the night rise “from the yard like a large bird.”

It is impossible to remain in a one-dimensional state when reading Chase’s poems, so quickly do her metaphors lead us into her conceptual worlds.

The first section ends with a bold seven-part poem called “Come to Bed.” Each short scene suggests eroticism. Through Chase’s well-placed lines the mind reels with possibility, as at the end of the first vignette:

You’ve never seen the inside

of my house, you’re in my bed

now, your tongue’s in my mouth

*

The power of suggestion is enormously effective throughout all of Chase’s poems. In “Last Night on the 40th-floor balcony,” the speaker imagines standing with “2 little girls / joking,” and through skillful detail has us right there with her,enjoying the scenary. Right before a horrific scene unfolds, we’re reminded that, “in dreams you can do this.”

The book’s second section moves outward, connected by a sense of being in less familiar surroundings. In “This is What it’s Like Going to A Language Poetry Poetry Reading,” Chase writes in a fiercely honest voice. The poem’s speaker tries hard to make sense of this new experience, but becomes increasingly bored and distracted. When the reader on stage informs the audience that her next poem will take 25 minutes to read, we understand completely the poem’s final stanza:

You think of killing her. You think she’s killing you,

You think of so much murder you’re scared to go to your car in the dark

Chase seems to be suggesting that we all have these thoughts,whether about a language poetry reading or something else, but the admission of such dark thoughts is what binds us together as human beings.

Ten of the eleven poems in the book’s third section refer directly to the dying or death of the speaker’s mother. Each takes on the theme of loss in some way, exploring and depicting the theme through telling details. Chase is never heavy-handed, maudlin or self-pitying. Instead, we are stroked gently with phrases and memories that keep us part of a continuum of life rather than separating us from what’s most sacred.

In “Beach Painting,” for example, “A bather [leaves] the painting, [walks] down the beach …/Others walk off into that same thick sea/with its here and now blues …”

One might be reminded of Walt Whitman here, and his ability to fuse the past, present and future, perhaps best displayed in his “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” Chase echoes Whitman even more in the book’s final section, composed entirely of the long, riveting “Kazimierz Square.”

Chase’s finest attributes are evident in “Kazimierz Square.” Time melds, imaginary figures and places entwine with the real. She is more bold and forceful than ever. “An actual tour through Poland,” Amy Clampitt comments in her foreword, “culminated in this demonic astonishment.” Chase does not hold back.

The reader is plunged into a mysterious, often ugly world, then lifted for a rest at just the right moments. Midway through the poem we remember, as if in a dream, that

There is enough light left in the sky to see

shapes of grape clusters in the vineyard.

[We] walk the trees between the fruit, distracted

by arbors turned colorless by night.

There is sugar in the sky.

It is difficult to ever wake completely from this extraordinary book of poems, nor does one want to. The images Chase creates etch themselves into our emotional landscape in lasting ways. Her words are palpable as “spuds/[that] taste of the ground/beneath//So I like words/how they grab hold/of the earth/with their underground/stock.” (“Rudimentary”)

————————————————————-

The Berkshire Eagle

(commentary)

The Problem of Self

November 1, 2000

by Richard Nunley

The current popularity of book groups is a social phenomenon I haven’t seen commented on very much. It shows that people still feel a need for the intellectual stimulation and life-enrichment yielded by living with a book over several days (or maybe weeks) and getting together with others to hash over what they got out of it, what they thought of it. I suppose it’s an old custom that has been revived by TV talk shows and pushed by publishers and book sellers, but that hardly makes it venal. Edith Wharton has an hilarious story, “Xingu,” about a Berkshire book group 100 years ago.

Before its budget was axed, the National Endowment for the Humanities funded state foundations which made grants to local libraries to host book discussion groups. Those I recall were quite popular, well worth the few hundred dollars each one cost. If the intent of the program was to spur citizens to do it themselves, the strategy seems to have worked. Now there are informal DIY book groups all over the place. If some members feel their group is “too much like school,” they are free to form their own group for a good wallow in romance. If others feel their group spends too much time gossiping, they can organize like-minded intellects for more serious discussions. Either way, it’s OK.

Recently I’ve been going to the book group my wife belongs to, which is currently reading “Paradise Lost.” I never tire of “Paradise Lost.” It seems to me that it’s much more a dramatization of the problem of self than it usually is presented as. By “problem of self,” I mean the problem every human, who is naturally the most important person in the universe to her/himself, has in coming to terms with the six billion or so other humans who are equally the most important person in the universe. Obviously, something has to give. One response to this problem is to say, “It’s not going to be me!” That is the response of Milton’s Satan. In Milton’s account, Satan proudly asserts that if his selfish will cannot be supreme, if it is he who has to give, then he would rather spoil and destroy any and all good. (Some people are like that.) Love angers him, torments him, excites his destructive spite. I can’t understand critics who contend that this twisted character is really Milton’s hero. Don’t they see that everything he says is false, his stirring eloquence empty fraud and deception? Don’t they see that Milton deliberately constructs him to portray the extreme of pride, to dramatize the psychology of the aggrieved, deluded self? Milton had a penetrating understanding of human pride. The person who has matured in years without maturing in reasonable understanding of the relationship of the self to others becomes either an arrogant tyrant or a servile doormat. (Our former rector used to say that a saint is somebody married to a martyr.) Emotional tyrants cannot bear any curb on their will, any slight to their pride. Much of what passes for “politics” these days is “self” getting its own back. As Milton shows, bilious anxiety for the self solves nothing, only creates misery. Self is the obsession of the 20th century, as much of its art and literature attests. This obsession has driven individuals farther and farther away from community into solitary anxiety, away from connecting with anything or anybody outside of themselves, and into inaccessible thickets of private fantasy and symbol unintelligible to others.

I have been reading “Kazimierz Square,” 35 poems by Karen Chase of Lenox, due to be published this month by Cavankerry Press ($14.) The Bookstore in Lenox may already have copies. These poems too seem concerned about this modern obsession with the self, and the connections between the pride of self and evil (e.g. , between Hitler’s Superman fantasies and Auschwitz, between Milosevic’s nationalistic arrogance and the agonies of the Balkans.) Her poems, as she warns, are not for the squeamish — few pretty odes to Berkshire wildflowers or moonlit snowscapes here. Some are sweatily erotic, some funny (“The ABC of What I’ve Been Called,” “Language Poetry Poetry Reading.”) Some are about mother’s ambivalence about daughters, and vice versa. Some are excruciating exposes of the heartlessness of modern selfish attitudes (“Last Night on the 40th Floor.”) Some capture the grim humor of the destitute in societies victimized by the monstrous, myopic — the satanic — selfishness of Leninism/Stalinism/Maoism.

Our modern “coolness” about dreadful things is perfectly caught in “Fishing the Wrecks.” Even the fantasy poems, which I don’t feel I understand very well, are studded with arresting images of modern selves — for example, the miner underground painting pictures of nature “from hearsay.” The title poem is a long sequence written as if to wild klezmer music — shrieking clarinets, frenzied strings evoking unrestrained abandon, sudden grief, a chaos of selves — dissonance, stinks, prayer, sex, hunger, animality, disease, anguish, elation, death, and prayer again. Sure and powerful stuff. I think an adventurous book group would get a lot out of a few sessions with “Kazimierz Square.”

—————————————————————

Radio

KAZIMIERZ SQUARE – The Faith Middleton Show WNPR Connecticut Public Radio

KAZIMIERZ SQUARE – The Roundtable WAMC Northeast Public Radio

KAZIMIERZ SQUARE – Morning Edition WFCR New England Public Radio

Excerpts

VENISON

Paul set the bags down, told how they had split

the deer apart, the ease of peeling it

simpler than skinning a fruit, how the buck

lay on the worktable, how they sawed

an anklebone off, the smell not rank.

The sun slipped into night.

Where are you I wondered as I grubbed

through cupboards for noodles at least.

Then came venison new with blood,

stray hair from the animal’s fur.

Excited, we cooked the meat.

Later, I dreamt against your human chest,

you cloaked me in your large arms, then

went for me the way you squander food sometimes.

By then, I was eating limbs in my sleep, somewhere

in the snow alone, survivor of a downed plane,

picking at the freshly dead. Whistles

of a far off flute — legs, gristle, juice.

I cracked an elbow against a rock, awoke.

Throughout the night, we consumed and consumed.

CIRCUS IN LUBLIN 1942

There was no music,

no one played the cimbalom

.Ladies dressed in largesized brassieres cheered

Yablo as he poured himself into a glass.

In formation, ducklings waddled around him, belching.

An odor of soup filled the tent.

Trained geese crooned to Yablo in Hungarian,

rugsellers told tales to noblemen,

lions turned puny.

A stench hung over all Lublin.

There were those who complained.

A bear walked across the stage in tears.

Flowers cracked open the floorboards,

grew before the crowd.

Fragrant roses, painted daisies, yellow iris.

Penguins marched out, placed ties around

the necks of plants.

Roseface, Daisyface, Irisface.

Against the upper reaches of the tent, parrots

fluttered ’til their feathers dropped.

Outdoors, from slagheaps, walls were built.

A great deal of crockery broke.

A fleshy woman sold mushrooms on the street.

Another, stray plums.

They placed tablecloths beneath their wares,

then newspaper, then the bowls of measly pears.

Men waited for word from anywhere.

ASPECTS OF LUCK

When a small

woman, such as

me, catches a large

fish, such as a 20

lb. salmon,

it is luck.

I am short, it bit, it

was luck, the fish was

big. I fought, it

fought, I felt big, I

drove quick

to Poulsbo to

have it smoked.

I have thought of good

fortune and luck, good

fortune and skill, and skill

and luck, but

luck it was and lucky too,

because I am short,

it was big,

we fought and now

,it is smoked.

Now that I’ve written

Aspects of Luck, it’s

next to the picture of me and

the fish, the question comes up of

which is worth more – god knows

the answer to that.

THE SWIM

Still she has her silent say.

I swam nude in a creek with my mother once,

we kept a distance.

Then she said how nice I looked. Sun

on her dark hair, wet curls on her neck,

she painted cadmium red canvases. My flesh

cushions my bones, when will we get over

her drawnout death? That creek has filled

with thawed snow, her lilies are beginning

to bloom, the sky now is begging for notice.

THIS CAN HAPPEN WHEN YOU’RE MARRIED

You find blue sheets the color of sky with

the feel of summer, they smell like clothes

drying on the line when you were small.

They feel unusual on your skin; you and your

husband sleep on them.

You find thick white towels that absorb

water. When you come from the bath, you are

cold for a moment, you think of snow for a moment,

you wrap yourself in a towel, dry off the water.

Now, you unpack your silver, after years, polish it,

set it in red quilted drawers your mother

lined for you when you were young.

You and your husband are in bed. The windows are open.

There is a smell from the lawn. It’s dark and late. You

and your husband are in the sheets. He is like a horse.

You are like grass he is grazing, you are his field. Or

he’s a cow in a barn, licking his calf. It’s raining out.

He gets up, walks to the other room. You listen

for his step, his breath. It is late. For moments

before you sleep, you hear him singing.

He comes to bed. He touches your face. He touches

your chin and lips. Later, he tells you this. He puts

his head on your breast. You are dreaming of Rousseau

now, paintings of girls and deserts and lions.

FISHING THE WRECKS

Six a. m. at Sheffield Arms,

the fishermen’s pub by the carpark,

our skipper Larry Ryan

orders a grease-out –

beans, eggs, and a slab of bacon that looks like ham.

“Eat,” says Larry”

We’ll be out for 8 or 10 hours.”

The waves are green in the Channel, a drizzle.

On shore are white humps of chalk.

Seven Sisters, the hills are called,

to the left, that cliff is Beachy Head. And

behind, the town of Battle where the Battle of Hastings was fought.

Larry Ryan’s radio is playing Verdi’s Requiem.

A fisherman puts live bait on his line,

“live bite,” he calls it. On comes Ode to Joy.

The fishermen are discussing

this particular rendition,

hauling in sea bass,

I am concentrating on my line.

“Virginia Woolf’s house is right off

Lewes-Newhaven Road” someone says,

baits his hook, dirty jokes over the shortwave mix with Berlioz.

We are fishing above torpedoed wrecks,

200 boats sunk by Germans in a ten mile radius.

Now they’re talking about Dunkirk.

I did not catch a fish.

“Do the wrecks have names?” I ask.

“Yes” – Larry’s reply.

“What do you call them?”

“Nothing – no-one’s business where I fish.

Hold this big bass up, I’ll take your picture.

You’re not a real fisherman until you lie.”