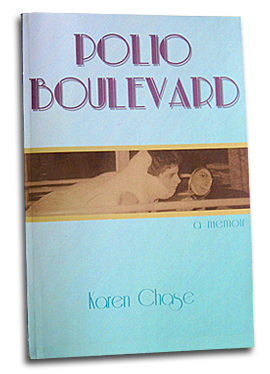

Polio Boulevard

“In the early ’50s, during the polio epidemic, I worked as a physical therapist. I saw firsthand the crushing suffering children and their families endured. I also saw their bravery and love for each other. Karen’s memoir is a truly remarkable piece of history.” – Olympia Dukakis

“Polio and poetry would seem to be near-opposites. Yet in Karen Chase’s compelling memoir of a terrifying disease she and so many others contracted in childhood, we watch polio’s unwelcome transformations to be matched and outdone by the twists and turns of a poet’s mind. Bravely and with surprising humor, Chase has turned the unlikely, the unlucky, even the tragic into beauty.” – Mary Jo Salter

In 1954, Karen Chase was a ten-year-old girl playing Monopoly in the polio ward when the radio blared out the news that Dr. Jonas Salk had developed the polio vaccine. The discovery came too late for her, and Polio Boulevard is Chase’s unique chronicle of her childhood while fighting polio. From her lively sickbed she experiences puppy love, applies to the Barbizon School of Modeling, and dreams of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a polio patient who became President of the United States. Chase, now an accomplished poet who survived her illness, tells a story that flows backward and forward in time from childhood to adulthood. Her imagination soars in this narrative of illness and recovery, a stunning blend of provocative reflection, humor, and pluck.

Read History News Network Interview

***

Reviews

LIBRARY JOURNAL review

POLIO BOULEVARD AT A HIGH SCHOOL article

BIOSUPPLY TRENDS QUARTERLY MAGAZINE profile

Interviews

RADIO

Listen to Karen on Public Radio’s 51%

Listen to Karen on Public Radio’s Midday Magazine

Guest Blog Posts

Excerpts

Everything leads me back to my polio days now. Last week I drove to a used bookstore on back roads to pick up a biography of Jonas Salk. I noticed a junky antique store, pulled over, puttered through. An old piece of furniture was chained to the store’s side porch – a hospital bed from upstate, where there had been a tuberculosis sanatorium long ago. It was oak and painted a darkish green. The works that made it go up and down were cast-iron and they were painted green too. The springs were spiraling. I fell in love with the bed and bought it.

The next morning, Memorial Day, I woke at six to meet the fellow who delivered the bed in his pickup. He unloaded it, I gave him a check, he left. I dragged the hose out, filled a pail with soapy water, scrubbed the thing down, and let it dry in the rising sun. The foam mattress in the basement just fit. I put a rose-colored sheet on it and dragged the bed under the maple tree. The day was just beginning.

Lying on this not-just-any bed brings me back to how full of motion the world was as I watched it from my polio bed. Everything but me seemed to be moving. I was immobilized in New York, high up on a hospital ward overlooking the East River. I was horizontal, covered in plaster, couldn’t get out of bed, couldn’t sit, couldn’t walk. I was flat. I had a view of the river and what I did was watch.

I watched boats pass from morning to night. I watched smoke billowing out of huge smokestacks, cars heading south on the FDR Drive, cars heading north, a helicopter flying across the sky, a jet carving a diagonal line across the blue as it took off from LaGuardia, boats moving, water moving. I watched the river’s current.

One day I was looking out the window when a submarine surfaced right in front of the hospital. It was sunny, I’m sure of it, and slowly the sub rose from the water. A bunch of uniformed sailors appeared on deck. Airy and light, it was the sight of victory.

From my bed, I would look out the window across the river to Queens as morning came. It would be barely dark. A light bulb would go on in a window and cast a sweet orange gleam – artificial, antiquated. I’d wonder about the person who turned the light on — why were they getting up so early, where were they going? I always had them going. They’d be going and I’d be watching.