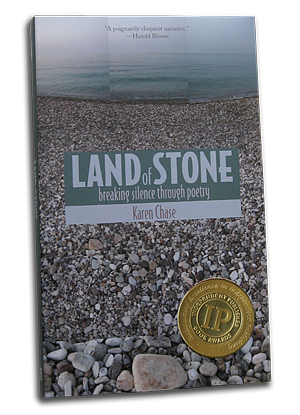

Land of Stone

“A poignantly eloquent narrative” – Harold Bloom

For more than a decade, Karen Chase taught poetry writing to severely incapacitated patients at a large psychiatric hospital outside of New York City. During that time, she began working with Ben, a handsome, formerly popular and athletic young man who had given up speaking and had withdrawn from social interaction. Meeting on the locked ward every week for two years, Chase and Ben passed a pad of paper back and forth, taking turns writing one line of poetry each, ultimately producing 180 poems that responded to, diverged from, and built on each other’s words.

Land of Stone (Wayne State University Press) is Chase’s account of writing with Ben, an experience that was deeply transformative for both poet and patient. In Chase’s engrossing narrative, readers will find inspiration in the power of writing to change and heal, as well as a compelling firsthand look at the relationship between poet and patient. As she tells of Ben’s struggle to come out of silence, Chase also recounts the issues in her own life that she confronts by writing with Ben, including her mother’s recent death and a childhood struggle with polio. Also, since poetry writing seems to reach Ben in a way that his clinical therapy cannot, Chase describes and analyzes Ben’s writing in detail to investigate the changes that appeared to be taking place in him as their work progressed. A separate section presents twenty-two poems that Chase wrote with Ben, selected to show his linguistic development over time, and a final section offers Chase’s thoughtful reflections on the creative process.

Chronogram Best Book 2007

Independent Publishers Book Awards, Bronze medal 2008

Reviews

Click here for interview with Karen

“Karen Chase’s Land of Stone is a poignantly eloquent narrative of the therapeutic relationship between an admirably humane, gifted poet and a schizophrenic young man. They write poems in collaboration, once a week for two years: each providing a line, the other responding. No miracle takes place, nor need ensue, but both are changed somewhat for the better. Chase is restrained and persuasive in telling her story.”

-Harold Bloom

Sterling Professor of Humanities, Yale University, Literary Critic

“The teacher is a poet, who understands the depths of helplessness from battles with childhood polio.Her student is a young man, sealed in a cocoon of silence by a series of traumas. In a psychiatric ward, they wrote poetry together, poet and patient, alternating with each other, one line at a time. This simple story is told with such honesty and force, chances are you will not put the book down until the last poem. Land of Stone is also a story of the many intimate roles that language plays in our lives, in the sounds and images it evokes.”

-William S-Y. Wang

Professor of Language Engineering,Chinese University of Hong Kong

“Karen Chase has invented a means of communication that is capable of stirring interest and communicative response even in a psychiatric patient who, for his own reasons, is determined not to be interested or responsive. The effectiveness of the quiet, elegant way, respectful of privacy, in which she invites interest and response makes the diagnostic interrogations and urgings to expression common in clinical work seem heavy-handed and primitive by comparison. In character, she does not presume to teach a lesson to clinicians, but there is one to be learned here nevertheless.”

-David Shapiro

Professor of Psychology, New School for Social Research,

and author of Neurotic Styles

“Land of Stone is a gripping, unusual book. I will hand-sell it until the cows come home!”

-Matthew Tannenbaum

Proprietor, The Bookstore in Lenox, Massachusetts

Radio

Patient Power – KVI-AM 570 in Seattle (Interview starts at 3:00)

WFCR News with Bob Paquette New England Public Radio

Interchange KPFT 90.1 – Pacifica Radio Houston (Interview starts at 14:00)

The Roundtable WAMC Northeast Public Radio

Video

A Sense of Oneself: Poetry in the Therapeutic Context – Podcast from The Philoctetes Center

LAND OF STONE launch at The Bookstore in Lenox, Massachusetts

Excerpts

– From the Preface

Land of Stone is a story about silence and kinship. For more than a decade, while continuing life as a practicing poet, I taught poetry writing to severely ill patients at Rosedale, a large psychiatric hospital outside of New York City. A man named Ben was a patient there in the mid-1980s. The story of how we worked together every week for two years, writing poems in near silence, goes against the grain of today’s culture and now bears tell- ing. To express one’s experience slowly and indirectly is a simple human need, but as we zoom through the twenty-first century, telling each exquisite detail of our lives with no regard for pace or privacy, talk—a lot of it and fast—is everywhere.

Strikingly handsome Ben had been admitted to the hospital by his parents, who had lived through the Ho- locaust. He had been virtually silent for six years and sometimes was violent. When I met him on the ward, he often stood rigidly in one spot with an intense gaze or would burst into a big grin at apparently nothing.

Ben’s family had moved back and forth between the United States and Israel several times. As a boy, Ben excelled in his schoolwork, loved art, and won trophies as a runner. In junior high, he began to take drugs. He was expelled from high school for disrupting classes by talking too much. And then, for some reason, Ben stopped speaking. When he was first admitted to a psychiatric hospital at age twenty-four, he was so with- drawn that he was described as autistic. Ben had given up on words.

We met every week in near silence and alternated writing lines of poems. I wrote a line. Ben wrote a line. We played off of each other’s lines like jazz players, improvising, doing solos, doing duets, never knowing what would come of it. With great hesitation, Ben chose to raise his voice—first on paper, then out loud. Eventually, he began to speak and became part of the talking world again.

Stories take a long time to tell. A few summers ago, I drove up the East Coast to Campobello Island. On a tour of Franklin Roosevelt’s summer cottage, a guide showed me his small bedroom with a simple, single bed and window. There, FDR had been stricken with polio. The night he fell ill, a forest fire was raging on the island. I pictured him slowing down, his muscles weakening, his head full of fever, his neck stiffening— Roosevelt gazing out that window as fire consumed the island. I could not sleep that night, or the next. Years earlier, as a young girl, I had been paralyzed from po- lio. Although I recovered, it was an experience I was silent about.

As I watched Ben slowly begin to tell his story through metaphoric poems, I understood just how long it can take for a person to be ready to tell his story. For the two years we worked together, it did not occur to me that I, too, had a story. Although I was the hos pital worker and Ben was the hospital patient, through our collaboration we both got better.

In fact, one day before I began work on the ward, a puzzling thing happened. I was on my way to the city branch of Rosedale for an interview, walking along the street toward the East River. It was cool, it was gor geous, it was spring, and aside from being nervous about the interview, I was feeling fine and fit. Pausing before a tree planted in a small square of dirt set in the concrete sidewalk, I—with no warning—began to vomit uncontrollably.

A few years later, during a meeting with the psychia trist who became my supervisor, I remembered that jarring day. As I told him the vomiting story, and as he questioned me, it dawned on me that I had been on my way to the very same hospital where, as a little girl, I had been a polio patient. Although it is hard to be lieve, until then I had failed to make the connection.

Since that first day when Ben and I began to write poems together, I had wondered what made our collaboration so magnetic. I wrote a line, Ben wrote a line—the phrase keeps recurring. Different from the dialogue that occurs in normal conversation, we offered each other intense attention, going back and forth, tak ing turns. As I wondered why I could collaborate with such a silent, stony character, I began to wonder about my own story as well as Ben’s.

What made this particular collaboration so powerful? Ben seemed locked inside himself. He looked immobile, although physically he was fine. As a child paralyzed from polio, I was locked out of myself. Not to equate mental and physical paralysis, but we shared a parallel sense of immobility that propelled our collaboration forward.

Although Ben had been sporadically violent, it was his six-year silence that caused his parents to bring him to Rosedale Hospital. By then in his late twenties, Ben barely spoke when he first entered the ward. He could be found standing sphinxlike in the corridor staring at the wall or in the bathroom taking showers. In his first hospital interview, he expressed the view that he had only been in his mother’s womb for three months before being born. Ben’s psychiatrist told me that he never spoke spontaneously and would answer ques tions with one word or, at most, a brief phrase. Never theless, Ben agreed to meet with me. We wrote nearly two hundred poems in collaboration, and every week for two years, I wrote a line, he wrote a line.